A detailed study of magnets built by MIT and Commonwealth Fusion Systems confirms they meet the requirements for an economic, compact fusion power plant.

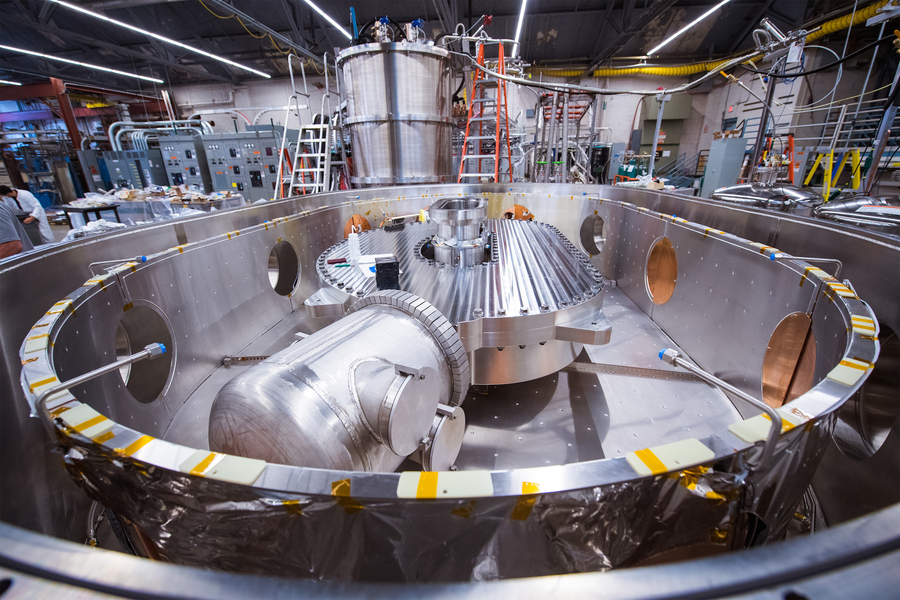

In the predawn hours of Sept. 5, 2021, engineers achieved a major milestone in the labs of MIT’s Plasma Science and Fusion Center (PSFC), when a new type of magnet, made from high-temperature superconducting material, achieved a world-record magnetic field strength of 20 teslas for a large-scale magnet. That’s the intensity needed to build a fusion power plant that is expected to produce a net output of power and potentially usher in an era of virtually limitless power production.

The test was immediately declared a success, having met all the criteria established for the design of the new fusion device, dubbed SPARC, for which the magnets are the key enabling technology.

All of this work has now culminated in a detailed report by researchers at PSFC and MIT spinout company Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS), published in a collection of six peer-reviewed papers in a special edition of the March issue of IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity. Together, the papers describe the design and fabrication of the magnet and the diagnostic equipment needed to evaluate its performance, as well as the lessons learned from the process. Overall, the team found, the predictions and computer modeling were spot-on, verifying that the magnet’s unique design elements could serve as the foundation for a fusion power plant.

Enabling practical fusion power

The successful test of the magnet, says Hitachi America Professor of Engineering Dennis Whyte, who recently stepped down as director of the PSFC, was “the most important thing, in my opinion, in the last 30 years of fusion research.”

Before the Sept. 5 demonstration, the best-available superconducting magnets were powerful enough to potentially achieve fusion energy (keep plasma heated to 100 million °C in isolation from the walls of the working chamber) — but only at sizes and costs that could never be practical or economically viable. Then, when the tests showed the practicality of such a strong magnet at a greatly reduced size, “overnight, it basically changed the cost per watt of a fusion reactor by a factor of almost 40 in one day,” Whyte says.

“Now fusion has a chance,” Whyte adds. Tokamaks, the most widely used design for experimental fusion devices, “have a chance, in my opinion, of being economical because you’ve got a quantum change in your ability, with the known confinement physics rules, about being able to greatly reduce the size and the cost of objects that would make fusion possible.”

The superconducting breakthrough

Fusion, the process of combining light atoms to form heavier ones, powers the sun and stars, but harnessing that process on Earth has proved to be a daunting challenge, with decades of hard work and many billions of dollars spent on experimental devices. The long-sought, but never yet achieved, goal is to build a fusion power plant that produces more energy than it consumes. Such a power plant could produce electricity without emitting greenhouse gases during operation, and generating very little radioactive waste. Fusion’s fuel, a form of hydrogen that can be derived from seawater, is virtually limitless.

But to make it work requires compressing the fuel at extraordinarily high temperatures and pressures, and since no known material could withstand such temperatures, the fuel must be held in place by extremely powerful magnetic fields. Producing such strong fields requires superconducting magnets, but all previous fusion magnets have been made with a superconducting material that requires frigid temperatures of about 4 degrees above absolute zero (4 kelvins, or -270 degrees Celsius). In the last few years, a newer material nicknamed REBCO, for rare-earth barium copper oxide, was added to fusion magnets, and allows them to operate at 20 kelvins, a temperature that despite being only 16 kelvins warmer, brings significant advantages in terms of material properties and practical engineering.

Taking advantage of this new higher-temperature superconducting material was not just a matter of substituting it in existing magnet designs. Instead, “it was a rework from the ground up of almost all the principles that you use to build superconducting magnets,” Whyte says. The new REBCO material is “extraordinarily different than the previous generation of superconductors. You’re not just going to adapt and replace, you’re actually going to innovate from the ground up.” The new papers in Transactions on Applied Superconductivity describe the details of that redesign process, now that patent protection is in place.

A key innovation: no insulation

One of the dramatic innovations, which had many others in the field skeptical of its chances of success, was the elimination of insulation around the thin, flat ribbons of superconducting tape that formed the magnet. Like virtually all electrical wires, conventional superconducting magnets are fully protected by insulating material to prevent short-circuits between the wires. But in the new magnet, the tape was left completely bare; the engineers relied on REBCO’s much greater conductivity to keep the current flowing through the material.

“When we started this project in 2018, the technology of using high-temperature superconductors to build large-scale high-field magnets was in its infancy,” says Zach Hartwig, the Robert N. Noyce Career Development Professor in the Department of Nuclear Science and Engineering. Hartwig has a co-appointment at the PSFC and is the head of its engineering group, which led the magnet development project. “The state of the art was small benchtop experiments, not really representative of what it takes to build a full-size thing. Our magnet development project started at benchtop scale and ended up at full scale in a short amount of time,” he adds, noting that the team built a 20,000-pound magnet that produced a steady, even magnetic field of just over 20 tesla — far beyond any such field ever produced at large scale.

Pushing to the limit … and beyond

The initial test, described in previous papers, proved that the design and manufacturing process not only worked but was highly stable — something that some researchers had doubted. The next two test runs, also performed in late 2021, then pushed the device to the limit by deliberately creating unstable conditions, including a complete shutoff of incoming power that can lead to a catastrophic overheating. Known as quenching, this is considered a worst-case scenario for the operation of such magnets, with the potential to destroy the equipment.

Later, during tests of the magnet at critical conditions, theoretical models of its behavior were tested up to partial destruction (melting of the winding). This was important for improving the design and testing the performance characteristics of electromagnets for use in future fusion reactors. The publication of development articles today became possible after receiving patents on the design of electromagnets and the principles of their operation. The study brings us closer to the moment when a man-made Sun can light up on Earth, and the energy in power grids will become endless and practically clean.

Source` https://news.mit.edu/2024/tests-show-high-temperature-superconducting-magnets-fusion-ready-0304

In the predawn hours of Sept. 5, 2021, engineers achieved a major milestone in the labs of MIT’s Plasma Science and Fusion Center (PSFC), when a new type of magnet, made from high-temperature superconducting material, achieved a world-record magnetic field strength of 20 teslas for a large-scale magnet. That’s the intensity needed to build a fusion power plant that is expected to produce a net output of power and potentially usher in an era of virtually limitless power production.

The test was immediately declared a success, having met all the criteria established for the design of the new fusion device, dubbed SPARC, for which the magnets are the key enabling technology.

All of this work has now culminated in a detailed report by researchers at PSFC and MIT spinout company Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS), published in a collection of six peer-reviewed papers in a special edition of the March issue of IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity. Together, the papers describe the design and fabrication of the magnet and the diagnostic equipment needed to evaluate its performance, as well as the lessons learned from the process. Overall, the team found, the predictions and computer modeling were spot-on, verifying that the magnet’s unique design elements could serve as the foundation for a fusion power plant.

Enabling practical fusion power

The successful test of the magnet, says Hitachi America Professor of Engineering Dennis Whyte, who recently stepped down as director of the PSFC, was “the most important thing, in my opinion, in the last 30 years of fusion research.”

Before the Sept. 5 demonstration, the best-available superconducting magnets were powerful enough to potentially achieve fusion energy (keep plasma heated to 100 million °C in isolation from the walls of the working chamber) — but only at sizes and costs that could never be practical or economically viable. Then, when the tests showed the practicality of such a strong magnet at a greatly reduced size, “overnight, it basically changed the cost per watt of a fusion reactor by a factor of almost 40 in one day,” Whyte says.

“Now fusion has a chance,” Whyte adds. Tokamaks, the most widely used design for experimental fusion devices, “have a chance, in my opinion, of being economical because you’ve got a quantum change in your ability, with the known confinement physics rules, about being able to greatly reduce the size and the cost of objects that would make fusion possible.”

The superconducting breakthrough

Fusion, the process of combining light atoms to form heavier ones, powers the sun and stars, but harnessing that process on Earth has proved to be a daunting challenge, with decades of hard work and many billions of dollars spent on experimental devices. The long-sought, but never yet achieved, goal is to build a fusion power plant that produces more energy than it consumes. Such a power plant could produce electricity without emitting greenhouse gases during operation, and generating very little radioactive waste. Fusion’s fuel, a form of hydrogen that can be derived from seawater, is virtually limitless.

But to make it work requires compressing the fuel at extraordinarily high temperatures and pressures, and since no known material could withstand such temperatures, the fuel must be held in place by extremely powerful magnetic fields. Producing such strong fields requires superconducting magnets, but all previous fusion magnets have been made with a superconducting material that requires frigid temperatures of about 4 degrees above absolute zero (4 kelvins, or -270 degrees Celsius). In the last few years, a newer material nicknamed REBCO, for rare-earth barium copper oxide, was added to fusion magnets, and allows them to operate at 20 kelvins, a temperature that despite being only 16 kelvins warmer, brings significant advantages in terms of material properties and practical engineering.

Taking advantage of this new higher-temperature superconducting material was not just a matter of substituting it in existing magnet designs. Instead, “it was a rework from the ground up of almost all the principles that you use to build superconducting magnets,” Whyte says. The new REBCO material is “extraordinarily different than the previous generation of superconductors. You’re not just going to adapt and replace, you’re actually going to innovate from the ground up.” The new papers in Transactions on Applied Superconductivity describe the details of that redesign process, now that patent protection is in place.

A key innovation: no insulation

One of the dramatic innovations, which had many others in the field skeptical of its chances of success, was the elimination of insulation around the thin, flat ribbons of superconducting tape that formed the magnet. Like virtually all electrical wires, conventional superconducting magnets are fully protected by insulating material to prevent short-circuits between the wires. But in the new magnet, the tape was left completely bare; the engineers relied on REBCO’s much greater conductivity to keep the current flowing through the material.

“When we started this project in 2018, the technology of using high-temperature superconductors to build large-scale high-field magnets was in its infancy,” says Zach Hartwig, the Robert N. Noyce Career Development Professor in the Department of Nuclear Science and Engineering. Hartwig has a co-appointment at the PSFC and is the head of its engineering group, which led the magnet development project. “The state of the art was small benchtop experiments, not really representative of what it takes to build a full-size thing. Our magnet development project started at benchtop scale and ended up at full scale in a short amount of time,” he adds, noting that the team built a 20,000-pound magnet that produced a steady, even magnetic field of just over 20 tesla — far beyond any such field ever produced at large scale.

Pushing to the limit … and beyond

The initial test, described in previous papers, proved that the design and manufacturing process not only worked but was highly stable — something that some researchers had doubted. The next two test runs, also performed in late 2021, then pushed the device to the limit by deliberately creating unstable conditions, including a complete shutoff of incoming power that can lead to a catastrophic overheating. Known as quenching, this is considered a worst-case scenario for the operation of such magnets, with the potential to destroy the equipment.

Later, during tests of the magnet at critical conditions, theoretical models of its behavior were tested up to partial destruction (melting of the winding). This was important for improving the design and testing the performance characteristics of electromagnets for use in future fusion reactors. The publication of development articles today became possible after receiving patents on the design of electromagnets and the principles of their operation. The study brings us closer to the moment when a man-made Sun can light up on Earth, and the energy in power grids will become endless and practically clean.

Source` https://news.mit.edu/2024/tests-show-high-temperature-superconducting-magnets-fusion-ready-0304